- Home

- Peggy Caravantes

The Many Faces of Josephine Baker Page 5

The Many Faces of Josephine Baker Read online

Page 5

Joséphine believed such generosity was a prelude to commitment. She decided she wanted to have a baby with him and broached the subject of marriage, conveniently forgetting she was still wed to Willie Baker.

Marcel squelched the idea. In blunt words, he told her that she was not his social equal and she was black—not marriage material for him. Devastated by his words, Joséphine lost her pep and energy. She became ill, and the doctor diagnosed bronchial pneumonia. In those days before the availability of penicillin, this was a serious disease. Joséphine developed a high fever and was confined to bed for three weeks. She gradually recovered and regained her strength. In October, she made her first record with Odeon Records, which included the song “Bye, Bye, Blackbird.”

Despite her recent illness, Joséphine spent her evenings partying in Montmartre, an area in Paris that nurtured most of the great artists and writers living in France at that time. It was in Montmartre that she met a man who had a great influence on her future. Giuseppe “Pepito” Abatino was a 37-year-old Italian bricklayer who had created a fake family history for himself and changed his name to Count Abatino. The fake royal title appealed to the ladies, with whom he was quite popular.

Of middle height with dark hair, a dark mustache, and dark eyes, Pepito wore a monocle and carried a walking cane, adding to his aura of sophistication. After meeting Joséphine, he pursued her with love notes during the day and escorted her to clubs and cabarets in the evenings. He flattered her and treated her like a lady—opening doors and pulling out chairs. Joséphine was charmed. He helped hold at bay her fear that she would disappear from the stage and be forgotten. Her mentor Bricktop did not like Pepito and advised Joséphine not to have a relationship with him.

MONTMARTRE

North of Paris on a 427-foot-high hill is Montmartre, which was once a rural village of vineyards and windmills. Montmartre means “mount of martyrs” and refers to the beheading of St. Denis, the first Paris bishop, in 250 AD. Initial settlers on Montmartre were refugees from Paris when Emperor Napoleon III gave much of the best land in the city to his wealthy friends.

Montmartre became a popular drinking area which began to attract artists, performers, and entertainment sites. Even as these groups took over Montmartre, it retained some of its distinct characteristics: old buildings; steep, narrow streets; and rustic windmills, some of which still operate today. Gradually, it became a working-class neighborhood, and by the time of the Paris World’s Fair in 1900, it had developed into an entertainment district with cabarets, dance halls, music halls, theaters, and circuses. Today Montmartre is a popular tourist destination.

As usual, the headstrong Joséphine ignored any advice, and Pepito became her manager and her lover. He decided she should not waste her time, energy, and money on frequenting other people’s clubs. He suggested she open her own establishment and he found a wealthy doctor to finance Chez Joséphine, which opened on December 14, 1926, in Pigalle, a tourist district in Paris. Customers flocked to the small club and paid exorbitant prices for the food just for a chance to be close to Joséphine and perhaps talk to her.

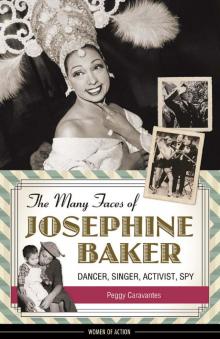

Joséphine Baker with Pepito (Count Abatino) after he became her manager and lover. © Bettmann/CORBIS

Her new manager never lost an opportunity to promote her, and he found a man to help Joséphine write her memoirs. Marcel Sauvage became the collaborator of her first book, Les Mémoires de Joséphine Baker, or The Memoirs of Joséphine Baker, while Paul Colin, the artist who created her first poster for the Revue Nègre, designed the book cover. Although she was only 21 years old, the memoirs portrayed her personality and contained opinions on a wide variety of subjects from her favorite meals to why she liked animals better than people. Like a child, she recalled gifts received: “I got sparkling rings as big as eggs, 150-year-old earrings that once belonged to a duchess, pearls like buck teeth, flower baskets from Italy … lots of stuffed animals … a pair of gold shoes, four fur coats, and bracelets with red stones for my arms and legs.” She also included recipes for meals that she had enjoyed as a child, such as corned beef hash and hotcakes. Some of her memories were inaccurate, such as her assertion that her parents were married (they were not). Other recollections were fanciful. In her dreams, kings walked with pointed shoes “and the queens were blond … sometimes I cried because I too would have liked to be a queen.”

Perhaps the most startling revelation of the memoir was her attitude about performing onstage. She said, “I am tired of this artificial life, weary of being spurred on by the footlights. The work of a star disgusts me now. Everything she must do, everything she must put up with at every moment, that star, disgusts me.” In commenting on the future, she predicted,

I will marry an average man. I will have children, plenty of pets. This is what I love. I want to live in peace surrounded by children and pets. But if one day one of my children wants to go into the music hall, I will strangle him with my own two hands, that I swear to you.

This reflected the conflict that Joséphine dealt with all her life. She longed for a happy home life but could not resist the footlights’ pull.

While she and Sauvage worked on her memoirs, Joséphine also starred in Un Vent de Folie, or A Wind of Madness, a second Folie production that Paul Derval produced with her as the star. The mixed audience reactions to Un Vent de Folie indicated that Joséphine’s popularity was slipping because people were tired of seeing the same type of performances. She received attention of a different sort in the spring of 1927, when she passed her driving test. The driving school where she had trained took out a full-page ad in the newspaper announcing that Joséphine had been their student.

In the evenings, after the Folie show, she went to Chez Joséphine, where she often sang—a prelude to her later career as a singer. Listening to her each night were her goat Toutoute and her pig Albert, who lived at the club. Of all the people who regularly came to her club, a famous writer named Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette was her favorite. Short and plump with short, frizzy hair and lips painted in a hard, thin line, Colette had no physical beauty to attract Joséphine to her, but earning the attention of the most famous female French writer of her time flattered Joséphine. She soon discovered she had much in common with the 52-year-old Colette, despite their age difference. Both had started in music halls, and both enjoyed shocking audiences, whether appearing nude or in lesbian scenes. Colette later dedicated a book to Joséphine, although it is not likely that Joséphine could have read much of it. The two became close friends and lovers in a relationship that lasted many years.

As Paris welcomed an influx of Americans, racial attitudes changed. One night while Joséphine sang, an American man shouted out that back in his country, she would be in the kitchen, not performing. That prejudice was infiltrating France became even more apparent when a hotel manager refused to rent Joséphine a suite because he feared her presence in the hotel would offend his American guests. Despite these unsettling incidents, Joséphine continued to work on new projects. She began a film called La Siréne Des Tropiques, or The Siren of the Tropics, but Joséphine did not enjoy the restrictions of filming as opposed to performing onstage. She resented having to confine her actions to a limited space and having to accommodate camera angles and lighting.

While she struggled with these demands, she received sad news about her favorite little sister: Willie Mae had become pregnant at 17 years old, and she died while trying to terminate the pregnancy. The frustration of making the movie and the grief over her sister caused Joséphine to become even more difficult to work with. Although rehearsals started on the set at nine in the morning, she’d arrive at five in the afternoon, storm into her dressing room, slam the door, and begin smashing makeup bottles against the wall. When someone once dared to ask what the matter was, she replied that her dog was sick.

Needing a new way to regain attention for Joséphine, she and Pepito announced that they had married at the American embassy on her 21st birthday. The marriage was as phony as Pepito’s title of C

ount. But Derval capitalized on the sham marriage by placing posters all over town claiming Joséphine was now a countess. She played her part well, acting the bubbly, giddy bride at a press conference: “I’m just as happy as I can be. I didn’t have any idea that getting married was exciting. I feel like I’m sitting on pins and needles. I am so thrilled.” To add to her remarks, she flashed a 16-carat diamond wedding ring that she claimed she could not wear often because of its weight. She also announced that the count had given her all the jewelry and heirlooms belonging to his royal family.

After finding no record of the marriage, French reporters doubted the story, but American papers picked it up with headlines proclaiming that a young black woman from St. Louis had become a countess. The June 22, 1927, issue of the Milwaukee Journal headlined: JOSEPHINE BAKER, BLACK DANCER, WEDS A REAL COUNT. They quoted Joséphine as saying: “He sure is a count. I looked him up in Rome. He’s got a great big family there with lots of coats of arms and everything.” This was good news for black Americans who still faced racial prejudice in the United States. Probably the most surprised person was Willie Baker, who read the story in the Chicago Defender. Despite what he may have thought, he did not challenge Joséphine’s apparent bigamy. Later some diligent reporters, having determined that there was no marriage record and that the count title was fake, learned that the whole episode was a publicity stunt. Joséphine dropped the countess title. By the time the sham was discovered, she had tired of what she was doing. Her contract with Derval for the Folies performances was coming to an end. Pepito decided to focus on making her as famous as possible, and he arranged a long tour to 25 countries in Europe and South America.

Before starting the tour, Joséphine gave a farewell show in Paris to demonstrate her development as a performer. In the first act, dressed in the torn shorts and ragged shirt of previous performances, she danced the Charleston. The audience seemed indifferent—they had seen it before. In the second act, however, she returned to the stage wearing a long, well-cut, red dress, and on her head she wore a fitted cloche studded with rhinestones. She sang in French for the first time and made a brief farewell speech, also in that language. She should have quit with the audience cheering her. Instead she began to thank all the people who had helped her. The long list was printed in the program, so it was not necessary for her to call them to the stage. At the intermission she further bored the audience by auctioning off five signed programs. By the time she got to the third one, catcalls and boos filled the theater.

Pepito hoped that Joséphine’s absence would return her to the hearts of the French people. While they toured, he planned to transform her into a proper lady by hiring language tutors, polishing her table manners, and teaching her the art of conversation. The couple departed France in January 1928, headed for their first stop in Vienna, Austria. Until their arrival in the city, they did not realize it was embroiled in political turmoil. A socialist government ruled the country, and 100,000 workers walked the streets looking for employment. Most of these workers were ready to unite with Germany because Austrians had begun to believe the ideas found in Adolf Hitler’s autobiographical manifesto, Mein Kampf, or My Struggle, in which he used insulting terms for black people, whom he considered inferior to whites. Before Joséphine ever arrived in Vienna, posters and flyers called her the “black devil,” and a petition circulated to prevent her performance.

Another group did not want Joséphine to perform in their city on moral grounds. Priests warned the large Catholic population to stay off the streets when she came so that they would not come into contact with her. To help people avoid her, St. Paul’s rang its church bells in warning as soon as her train arrived in the city. On the way to her hotel in a horse-drawn carriage, Joséphine was frightened to see protestors lining the streets. They brought back memories of her childhood and the East St. Louis riots when she was 11.

The city council refused to let Joséphine perform at the Ronacher Theater as previously scheduled, so Pepito booked her at another, smaller theater, the Johann Strauss. Since it was not available until four weeks later, they used the extra time to explore Vienna and for Joséphine to learn how to ski at a nearby alpine resort.

Despite the protests, many Viennese welcomed her on opening night. The theater was filled and continued to be so for the next three weeks. Instead of appearing onstage in the banana skirt expected by the audience, Joséphine wore a long cream dress buttoned up to the neck and sang a simple spiritual, “Pretty Little Baby,” in English. The audience applauded and rose to their feet. After she opened the show with such a demure performance, they accepted the other acts in which she danced more provocatively.

The next stop was the jazz-loving city of Prague, where a huge crowd welcomed Joséphine at the train station. As she tried to move from the train to her limousine, her fans stampeded to see her. She jumped on top of the car to avoid being crushed. The incident frightened her, but she stayed on the car’s roof as she rode through the town, waving to the crowds. At the theater, when she concluded her last act, the audience threw rabbit feet on the stage. It was well known that Joséphine always carried a rabbit foot with her for good luck, and her audience wanted to increase her luck with their gifts.

Joséphine loved Budapest, where again, such large crowds welcomed her that she hid in a hay wagon to get away. However, not everyone wanted her to perform in their city, which at that time battled widespread poverty. On opening night, angry militant students threw ammonia bombs on the stage when she appeared at the Royal Orpheum Theater. They resented a foreigner making so much money when there were so many poor people in their country. The incident alarmed Joséphine, but she did not stop her performance. The following day, Pepito added to the publicity surrounding the agitators’ actions by having Joséphine ride through downtown Budapest in a small buggy pulled by an ostrich. Thankfully Joséphine did not encounter any more explosive receptions after leaving Budapest. In Stockholm, the entire royal family, headed by the Crown Prince of Sweden, came to see her show. When asked what the Crown Prince looked like, Joséphine said, “I couldn’t tell you. When I dance, I dance. I don’t look at anyone, not even a king.”

As they moved on, a tragedy occurred in Zagreb, Croatia. Alexius Groth, a 21-year-old draftsman, first saw Joséphine in Budapest and was so fascinated by her that he followed her tour. He flooded her with flowers and love notes, but she ignored him. One night as she left a nightclub, the young man walked right up to her and pulled out a knife. Instead of using it on Joséphine, Alexius stabbed himself and fell at her feet. The New York Times reported: “He wounded himself severely but may recover.” Once again Joséphine was thoroughly frightened by her fans’ reaction to her, but she continued to perform nonetheless.

The tour’s last stop in Europe was Amsterdam, where enthusiastic crowds jammed the streets for two hours. Joséphine danced the Charleston in Dutch clogs, and her performance was so successful that the show was booked for twice as long as originally planned.

Joséphine and Pepito went back to Paris in the summer of 1929. They immediately visited the newspaper offices to make sure everyone knew she had returned and to show them how well she could speak French. Even though Joséphine had to complete her tour, she told the newsmen, “I don’t want to live without Paris. It’s my country. The Charleston, the bananas—finished. Understand? I have to be worthy of Paris. I want to become an artist.”

5

Two Loves

IN THE SAME YEAR THAT THE Great Depression began in America, Joséphine bought a mansion in Le Vésinet, a suburb about 15 miles from the heart of Paris. Called Le Beau Chêne, or The Beautiful Oak, the 30-room, red-and-gray, brick house sat on extensive grounds covered with stately oaks. High metal gates guarded the entrance to a long white gravel driveway leading to the house that looked like a castle, with its turrets and dormer windows. The spacious grounds also included a formal garden, a terrace, a greenhouse, several lily ponds filled with goldfish, and enough land for Joséphine’s mena

gerie of animals: dogs, cats, monkeys, parrots, parakeets, cockatiels, rabbits, piglets, turtles, ducks, chickens, geese, pigeons, pheasants, and turkeys.

To Joséphine, Le Beau Chêne was a dream come true. Her friend Bricktop said, “Joséphine had to have been here before as a queen or something. She traipsed around her château just like she always lived this way… I think she thought she was Napoleon’s Josephine.”

To get rid of the mansion’s interior gloominess, Joséphine remodeled and decorated each room in a unique design, from the style of Louis XVI to East Indian decor. In her own suite, she placed a silver-plated bathtub. For furnishings, she purchased antiques, such as a 15th-century suit of armor for the entrance hall. She hired three gardeners and gave them their first assignment: across the terrace, spell out JOSÉPHINE BAKER, using yellow- and red-leafed coleus plants.

Before she completed the plans for the new home, Joséphine and Pepito sailed for South America to finish her world tour. This voyage, in which she stayed in a first-class cabin, differed greatly from the one four years earlier, when she traveled from the United States to France in steerage on the Berengaria. Joséphine expected to find racial tolerance in South America, but when she and Pepito docked in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in the summer of 1929, she was shocked to discover that she was a source of controversy. Demonstrators protesting her presence mingled in the streets with people who were anti-government. Protestors for one cause or another seemed to be everywhere.

On opening night, agitators from both groups filled the theater. They hurled abusive language at each other and threw firecrackers, many of which landed on the stage. Joséphine huddled in fear behind the stage curtains. The orchestra kept on playing until the disruption ceased. Then Joséphine danced before a full house of 2,500 people. After that, the theater sold out for every night of her performances, leading her to feel that much of the protest concerned her race, not her dancing. The trip marked a turning point for her. For the first time, she recognized that racial prejudice was not limited to the United States. That realization affected the rest of her life. She became determined to prove that all people, regardless of race, should be treated the same because they were all part of one family. Skin color should not matter.

The Many Faces of Josephine Baker

The Many Faces of Josephine Baker